InTuition taster: Shades of grey

The digital media age has made it even harder for people to distinguish between real and fake news, and everything in between. That only makes it all the more important that critical literacy skills are taught from a young age, says Stacey Stevens.

In the modern age, our increasing reliance on digital information sources is well documented. In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, the implications of this, as well as the role of social media and the 24-hour news cycle, have been drawn into sharp focus.

In May 2020, two months into the first UK lockdown, a survey found more than a fifth of people in England thought the coronavirus was a hoax (University of Oxford, 2020, cited in Young, 2020). By March 2021, YouTube had removed more than 30,000 videos within five months that contained misinformation regarding Covid-19 vaccinations (BBC, 2021).

Against this backdrop, a report by the National Literacy Trust found that only two per cent of children and young people had the critical literacy skills they required to tell a fake news story from a real one. Correspondingly, 54 per cent of teachers believed the National Curriculum did not equip children with the literacy skills they needed to identify fake news (National Literacy Trust, 2018).

Critical literacy

Critical literacy is the ability of a reader to understand a text in its social and historical context, including the dynamic between themselves and the author, rather than absorbing it in a passive manner. (Freire, 1970).

This research focused on two specific models of critical literacy. Firstly, the ‘four resources’ model of Luke and Freebody (1999), which champions learners fostering four essential roles:

- Code-breaking: recognising the fundamental structure of written texts and using this to break down the information within them

- Meaning-making: comprehending and creating meaningful texts in a variety of formats using an understanding of literal and inferential detail

- Text-using: using texts in functional ways and distinguishing purpose

- Text-analysing: critically analysing texts and acknowledging the perspectives and influence inherent in them, including the identification of bias and reflecting on an issue from different points of view

The second model, adopted by Hinrichsen and Coombs (2013), updated this framework to embed digital elements within critical literacy by expanding the four original resources. Accordingly, the role of code-breaking became ‘decoding’: enhancing the breakdown of textual structure to include the conventions and lexical fields of digital formats. Meaning-making was updated to incorporate an understanding of the hypertextual nature of digital and network-based texts, as well as the added complexity of interpersonal interactions in online communities.

Text-using was adapted to take into account the shift from specialist and organisationally controlled practices to individual and group production of texts, as well as the wide availability of presentational design options and various format creation tools, resulting in a need to be aware of more fluid and constantly developing conventions.

Additionally, text-analysing was extended to consider the issue of anonymous digital authors in online spheres, and the vital role critical evaluation plays in establishing the validity of content created online as well as the ideology behind it. In terms of digital text production, Hinrichson and Coombs note the “legal, ethical and moral decision-making” now required. Finally, the four updated resources were supplemented by a fifth, ‘persona’, in which learners would need to develop an understanding of online personae in different contexts and acknowledge their role as participants and co-creators.

Further investigation

As an English lecturer at a further education and training college, I was intrigued as to why critical literacy remained problematic for young people in the UK and what role the English Language GCSE played in instilling critical literacy skills in the digital age.

My research took place in two West Yorkshire further education and training colleges, with teachers of learners aged 16-19 undertaking GCSE English Language. These learners have not achieved a Grade 4 at school or in their previous educational institutions, and are retaking the exams for perhaps the first or second time.

A case study was chosen in order to generate the rich data needed to illuminate teachers’ personal experiences and perspectives. To increase the validity of the findings, a mixed methods approach was taken. A survey was distributed to teachers in both institutions, with a selection of closed questions and one optional open question for additional information. This ensured that data was clear and concise, enabling patterns to be observed with validity and reliability.

A semi-structured interview was then created, with a list of 12 probe questions to guide the discussion while encouraging respondents to elaborate on the subject matter in an open and individualistic way. There were three essential themes: barriers and approaches; the impact of the digital media age; and curriculum. From the nine respondents to the initial survey, four individuals self-selected to participate in the interviews.

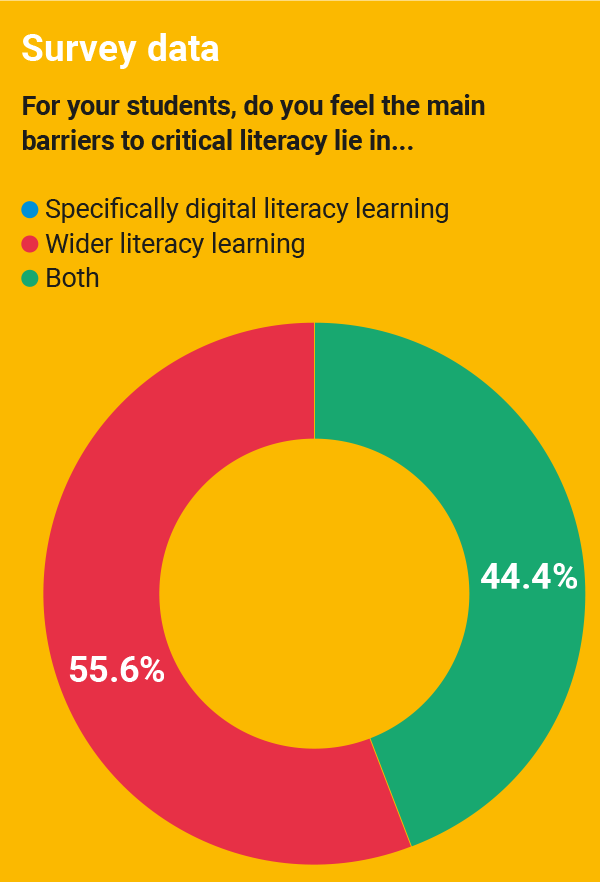

Findings: barriers to critical literacy

One of the key findings was the general agreement that wider literacy skills remained a central barrier to critical literacy development in the digital age. While all respondents noted the significant role digital literacy had to play, wider literacy skills persisted as a major obstacle in the teaching and learning of critical literacy.

The research also found that the digital era itself generated considerable barriers for learners in terms of their critical literacy. People may now have more choice in the sources of information they access and the stories they read, but with this power shift comes the potential for young people to limit their exposure to topics beyond their immediate interest. Respondents observed that this ‘echo chamber’, created either knowingly by the individual or through algorithmic direction by search engines or social media, resulted in learners who lacked the ability or willingness to access texts with difficult or unusual topics, and who were therefore unable to critically assess them.

Additionally, respondents claimed learners were unwilling or unable to access long-form text due to their being accustomed to short-form digital literature. This may be seen as a further consequence of the internet ‘rabbit hole’, but may also be drawn from the impact of an excess of information; in the face of limitless data, many young people perhaps respond by absorbing less.

In the ‘post-truth’ era, interview respondents reported their learners’ general distrust, both of media and organisations. As a result, conspiracy theories and misinformation were commonly referred to and believed by their learners, with implications for their health and wellbeing. One participant noted the tendency to rely on “social consensus”, with learners’ views often “biased to what their parents think, what the people around them think”, while another claimed to have six or seven learners in one teaching group who “thought the whole Covid thing was a load of rubbish” due to what they had read online in social media spheres.

Respondents gave a mixed view of the opportunities the GCSE curriculum provides to develop critical literacy skills. Where some participants spoke of finding the opportunities inherent in the curriculum in terms of text choice and approaches in the classroom, others lamented the rigid devotion to older text forms and historic literature. This approach, it was argued, further held learners back from accessing the context of the literature. In addition, the criteria for Grade 4 was challenged, with respondents noting that critical skills generally fell within the higher grading requirements, meaning learners were able to achieve the passing grade without necessarily gaining a good standard of critical literacy.

Developmental factors

The finding that many learners enter further education without a good standard of general literacy is, of course, not ground-breaking. The factors that affect the development of an individual learner’s literacy are numerous: SEND needs and how these have been met are one clear consideration; attendance and engagement in literacy education are another. But research suggests parental involvement in activities pertaining to a child’s literacy is the most important factor in linguistic development, with family participation in a child’s school life deemed to be the major predictor of achievement at 16 years old (McCoy and Cole, 2011).

A major consideration for further education and training educators is the attainment gap for disadvantaged learners, with twice the number of 16- to 18-year-olds from lower socioeconomic backgrounds attending further education colleges than sixth forms (Social Mobility Commission, 2019). By the time they finish compulsory education, children from disadvantaged backgrounds in England are typically around three years behind the highest income learners in their reading skills (Jerrim and Shure, 2016).

Disruption resulting from Covid-19 has only exacerbated the issue. Secondary schools with higher proportions of disadvantaged learners have apparently experienced 50 per cent greater learning losses than those serving higher-income communities (Department for Education, 2021b, cited in National Literacy Trust, 2022), as well as an extra month of learning loss specifically in reading (Department for Education 2021b, cited in National Literacy Trust, 2022).

Further education and training is perhaps seen as a safety net for those who do not attain Grade 4 at GCSE the first time around, but learners can only make up so much ground if they have not gained a sufficient base of general literacy proficiency when they enter our classrooms. Against this backdrop, the study highlighted approaches further education and training educators can take to best support their learners in overcoming barriers to critical literacy.

Taking action

The key approach educators advocated for overcoming barriers in the classroom puts the learner at the centre of teaching and learning practice. Rather than trying to make the learner fit the curriculum, respondents reported their efforts in making the curriculum fit the learner. Participants explained how they mirrored their learners’ short-form online interactions by cutting long-form extracts into shorter-form excerpts, or asking learners to access one element of the text as opposed to an overarching theme. In this way, teaching and learning was designed around developing the same skills in a more accessible format.

Where learners may be reluctant to access texts outside of historical and social contexts with which they are familiar, respondents recommended drawing comparisons between issues and concerns from the past and those of the modern world. Respondents argued that text choice is paramount, and the ability to choose fiction and non-fiction literature that reflects the experiences and interests of learners as closely as possible, while still meeting the requirements of the curriculum, was deemed vital. Clearly, there is also a need to ensure a range of digital texts is included in any contemporary curriculum.

Further to this, participants spoke of the importance of harnessing their learners’ strengths through co-creation of learning activities. By centring learning around what learners could do, critical literacy skills could be embedded in learners’ existing skillsets.

Respondents recommended there should be regular opportunities for learners to conduct scaffolded independent internet research, followed by in-depth discussion of their findings as a class. A whole-group debate format was particularly favoured, helping learners to develop confidence in their voices and embedding opportunities to question and compare perspectives, recognising inconsistent representations of the issues at hand.

Respondents spoke of the importance of building a supportive atmosphere in the classroom

The vital element of such activities in terms of critical literacy development would be in training learners to examine the validity of the information they find. Encouraging learners to check sources, search for context around an issue, and check who is sharing the information and what their motivation might be serves to develop skills in recognising disinformation and misinformation when reading outside the classroom. The Education and Training Foundation’s Enhance Digital Teaching Platform provides numerous resources to support teachers and learners in this endeavour.

Giving learners the space and support needed to question and debate was also recommended in tackling the echo chamber of digital information sources. If there is indeed a growing culture that is highly influenced by online communities and practices, and in which questions that may lead to difficult or uncomfortable discussions are ostensibly discouraged and polarised black-and-white views are promoted, the classroom must be the place to counteract this.

Respondents spoke of the importance of building a supportive atmosphere in the classroom, in which learners could feel comfortable and confident in sharing their thoughts and ideas – and, vitally, where these could be challenged without either party fearing reprimand or ridicule.

Stacey Stevens is an English lecturer at Shipley College in Saltaire, West Yorkshire

References and further reading

BBC (2021) YouTube deletes 30,000 vaccine misinfo videos. BBC News online, 12 March 2021.

Available at: www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-56372184

Clark C and Picton I. (2021) Children and young people’s reading engagement in 2021: Emerging insight into the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on reading. Available at: https://cdn.literacytrust.org.uk/media/documents/Reading_in_2021.pdf

Department for Education (2013) English language GCSE subject content and assessment objectives. Available from: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/254497/GCSE_English_language.pdf

Department for Education (2021a) The reading framework: teaching the foundations of literacy. Available at: http://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-reading-framework-teaching-the-foundations-of-literacy

Department for Education (2021b) Understanding progress in the 2020/21 academic year: complete findings from the Autumn term. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pupils-progress-in-the-2020-to-2022-academic-years

Freire P. (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin Modern Classics. Hinrichsen J and Coombs A. (2013) The five resources of critical digital literacy: a framework for curriculum integration. Research in Learning Technology, 21.

Available at: doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v21.21334

House of Lords (2020) Digital Technology and the Resurrection of Trust. House of Lords. Available at: committees.parliament.uk/publications/1634/documents/17731/default/

Jerrim J and Shure N. (2016) Achievement of 15-year-olds in England: PISA 2015 national report. Available at: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/574925/PISA-2015_England_Report.pdf

Luke A and Freebody P. (1999) A map of possible practices: Further notes on the four resources model. Practically Primary, 4(2), 5-8.

McCoy E and Cole J. (2011) A snapshot of local support for literacy: 2010 survey. London: National Literacy Trust.

National Learning and Work Institute (2016) Skills and poverty Building an anti-poverty learning and skills system. Available at: learningandwork.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Skills-and-Poverty-building-an-anti-poverty-learning-and-skills-system.pdf

National Literacy Trust (2018) Fake news and critical literacy. National Literacy Trust.

National Literacy Trust (2022) COVID-19 and literacy: The attainment gap and learning loss. Available at: literacytrust.org.uk/information/what-is-literacy/covid-19-and-literacy/covid-19-and-literacy-the-attainment-gap-and-learning-loss

Social Mobility Commission (2019) State of the nation 2018-19: social mobility in Great Britain. Available at: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/798404/SMC_State_of_the_Nation_Report_2018-19.pdf.

University of Oxford (2020), cited in Young S. (2020) Coronavirus: more than a fifth of people in England believe Covid-19 is a hoax. The Independent,. 22 May 2020. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/coronavirus-conspiracy-theories-hoax-government-misleading-man-made-survey-a9527876.html